Preservation and Access

After the analog media formats (film and VHS), the first digital version of “Black God, White Devil” was released in 2002, when a scanning process of the original negative was carried out in a standard format.

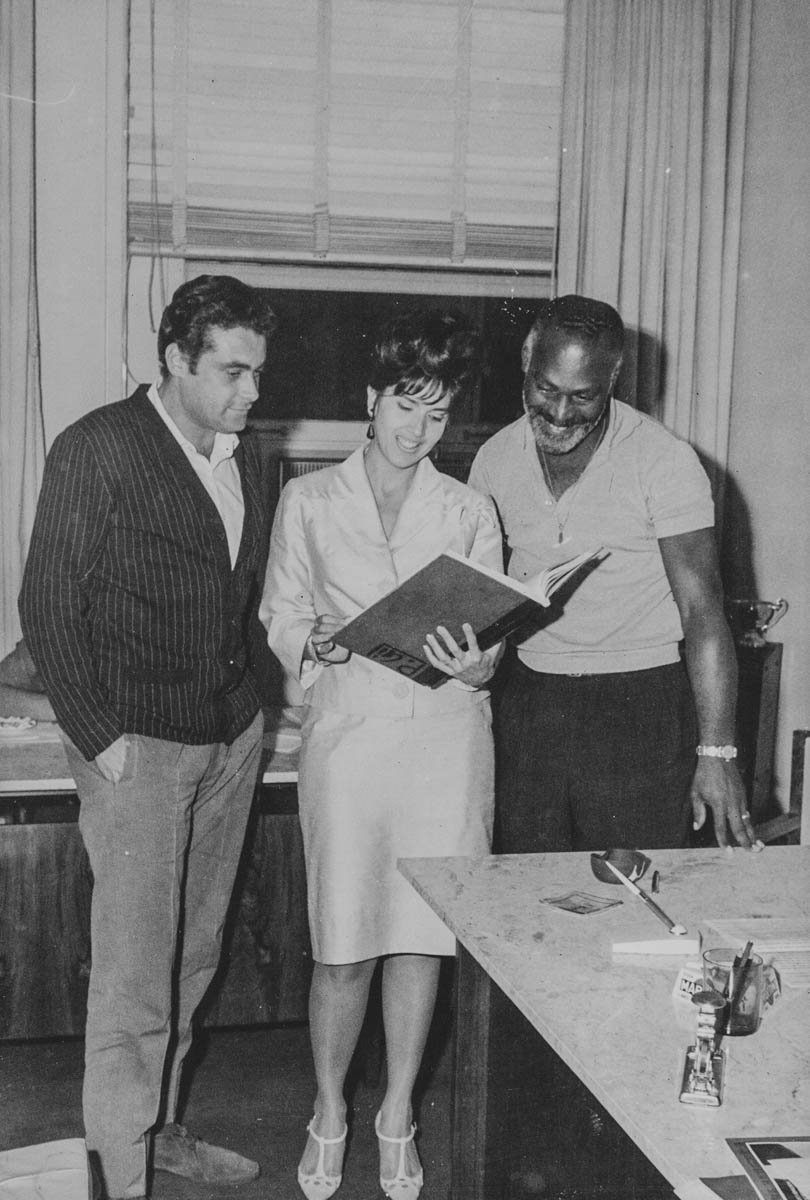

“At the time, we barely had the technology available for that,” says Paloma Rocha. “It generated a lot of controversy. I was attacked by many people who said that a DVD would never replace film. But I wanted people to be able to watch the film, and there was federal funding for that via Petrobras (the national oil company). This film started digital restoration in Brazil”, she boasts.

The project was directed by Paloma and her producer, in partnership with the Tempo Glauber institution, which preserves, researches and stores her father’s collection. “That was the first time film was scanned digitally here in the country. Some films were eventually scanned in 2K,” recalls Paloma.

When talking about the restoration of a film, some concepts remain little understood by most audiences, even cinephiles. The first and most important one is film preservation. “Black God, White Devil” is one of the more than 250 thousand rolls of prints maintained by the Cinemateca Brasileira.

Though it is trying to keep the lights on in this critical time, the institution charged with caring for the memory of Brazilian is a reference around the world in its tutelage of the film production. That practice encompasses more than the mere cataloguing and storage within the building, originally erected as a meat-packing plant in Vila Clementino, in São Paulo.

Rodrigo Mercês, Preservation Coordinator at the Cinemateca Brasileira, teaches that preservation is not limited to guarding, but also in providing access to the preserved materials. “Preserving a work of art can’t be just about keeping it safe, but also adapting it to constantly changing technology in viewing habits”, he says.

In other words, a lot was said about “Black God, White Devil” being preserved, an allusion to the 35mm print kept in the institution; it is inaccessible, however, by current digital technology. “The work was only accessible in photochemical technology, until now, there was no preservation in digital formats”, he ponders.

For Mercês, there is a consensus that the digital medium is not the most suitable for storing materials in the long term. Therefore, the 35mm copy deposited at the Cinemateca Brasileira is still the best way to keep the work’s integrity unaltered.

“We will continue to keep it stored and preserved, with any and all best practices. We have taken it out of storage in order to generate a digital matrix that can be duplicated and shown to viewers. In the future, technology will change again, and if a new matrix is needed, they’ll use the original print once again. It lasts for decades”, he says.

That durability depends on the sustainability of storage conditions. “The migration process must be constant and continuous. In our current doomsday scenario, everything preserved in our warehouse can still be migrated to digital formats. But time keeps on ticking, and it is even more complicated if we are to use storage tapes like LTO magnetic technology.”

To restore “Black God, White Devil”, the team coordinated by Paloma Rocha sought to be faithful to technical standards. “The process followed current best practices, using the best possible storage materials (files with specifications aimed at greater durability) and better access formats (current technological supports, such as digital projectors, international streaming standards and blurays)”, guarantees Rodrigo Mercês.

Luís Abramo adds that the restoration process essentially seeks to preserve the film’s memory. “And memory is not only what is in the negative, but in the methods of production employed to make the film”, he says.

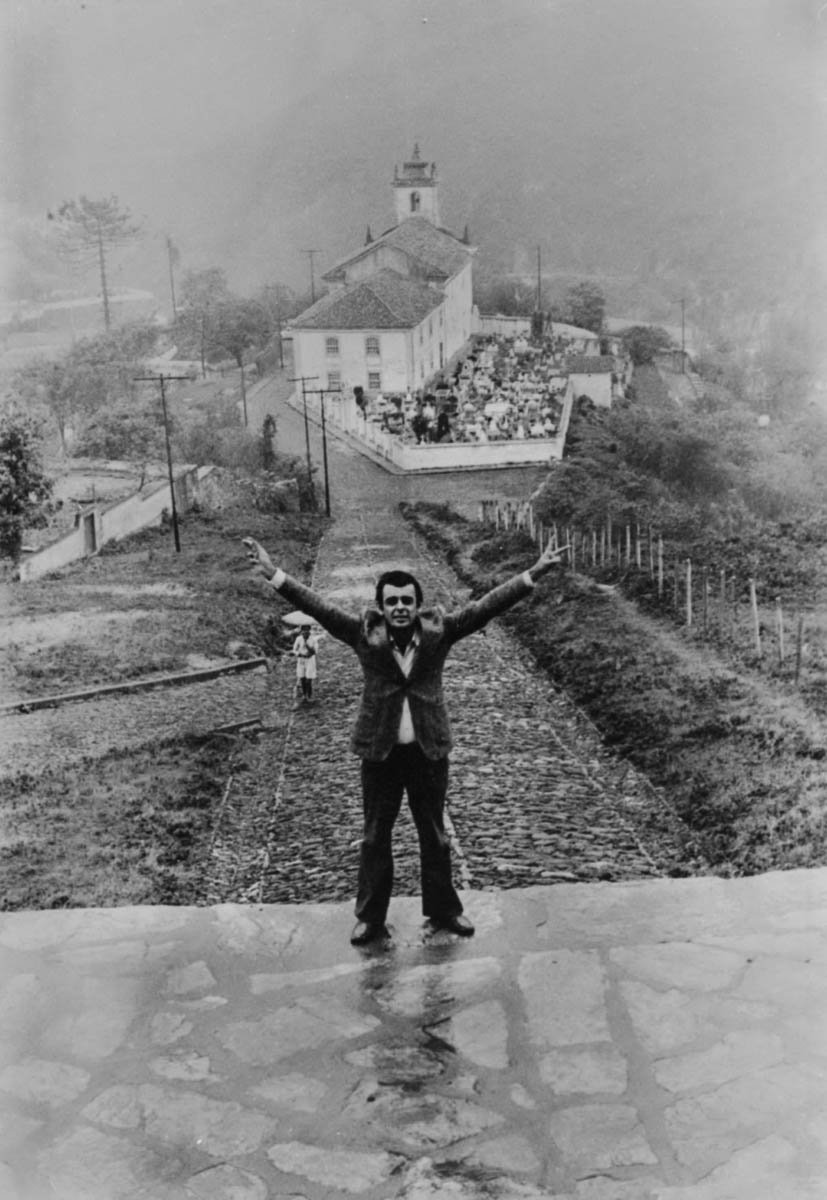

The biggest challenge, according to him, will be taking the film to different formats, theaters, and projectors. “It’s like a brand new film. Very potent and sure to provoke a lot of debate going forward. We are committing to the future. It’s not just about preservation, but also showing the film and inspiring generations.”

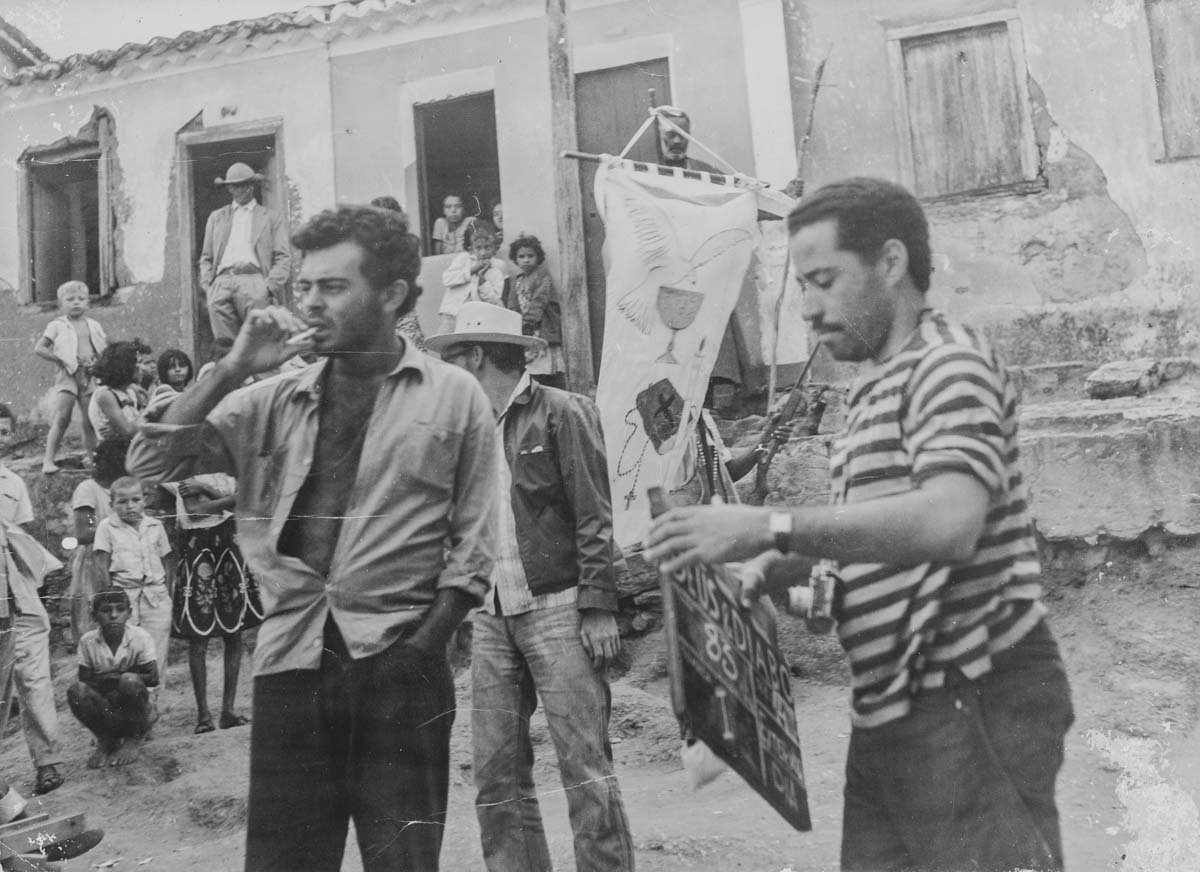

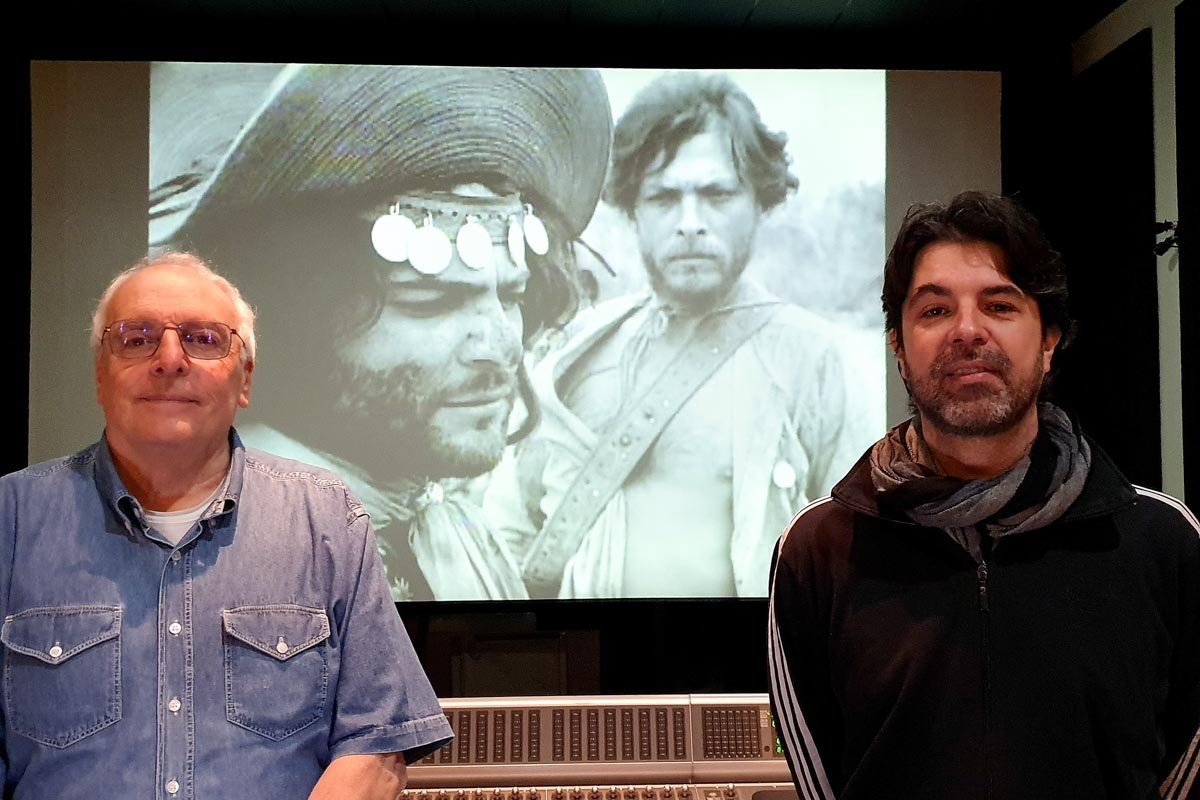

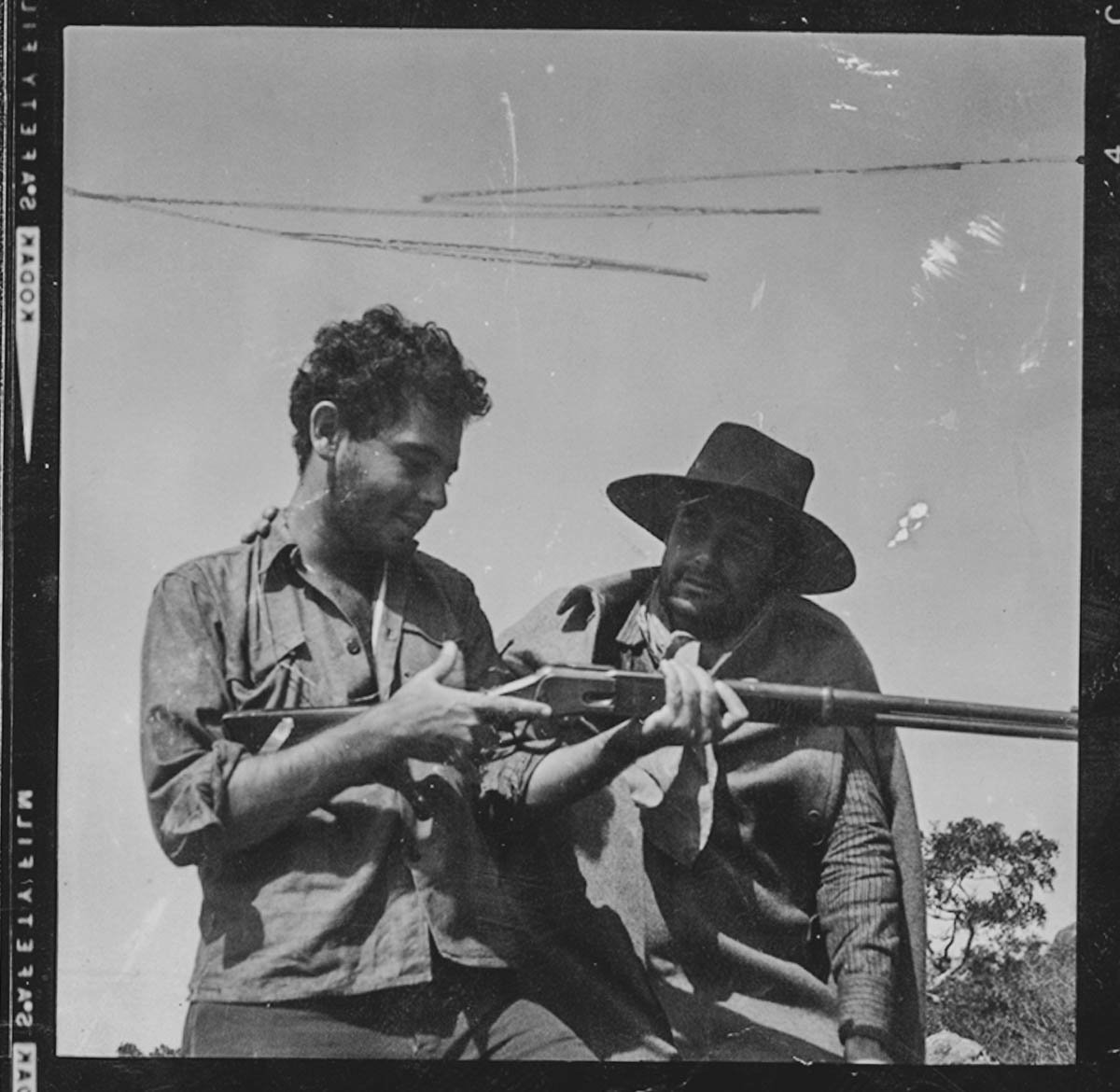

Glauber Rocha (holding rifle) and Mauricio do Valle

The Light and the Image

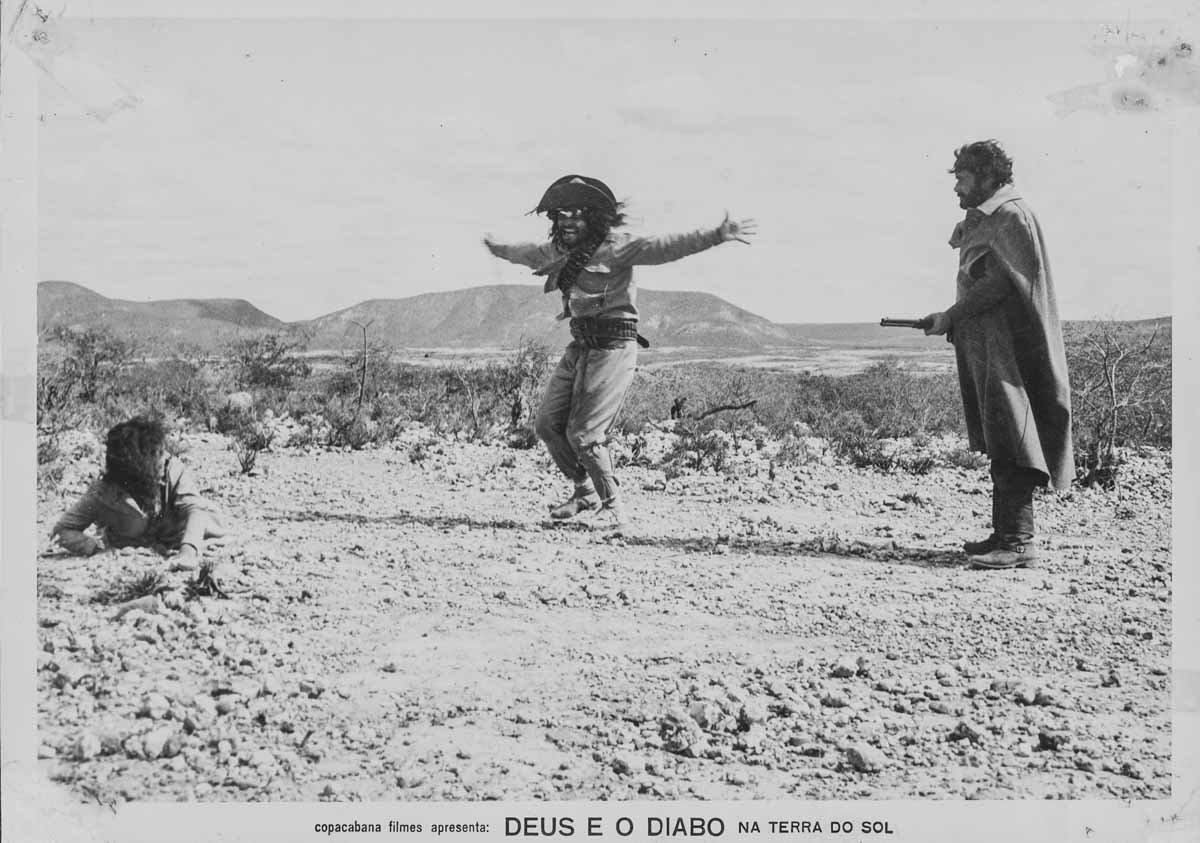

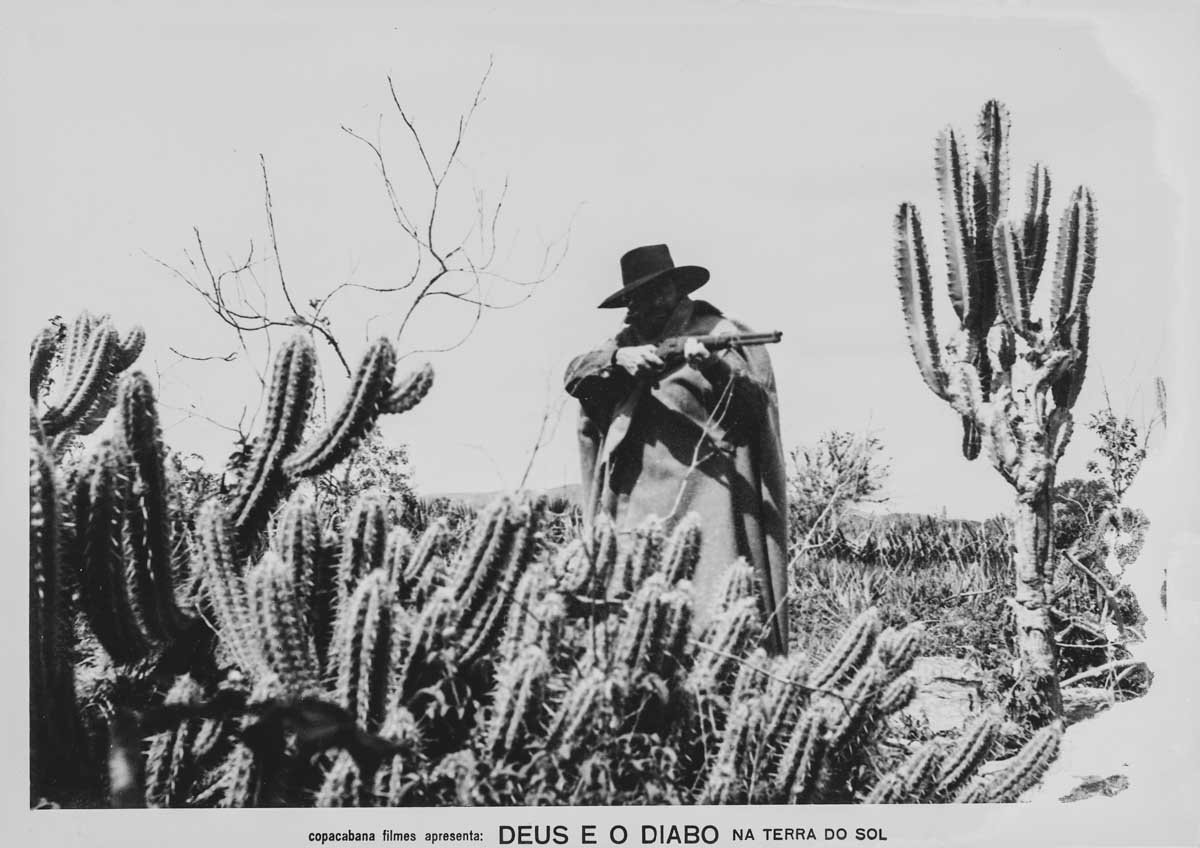

No matter how complex the attributes of a film, it is the image that usually predominates. “Black God, White Devil” carries nuances of light, contrasting and framing, which underscore a whole new concept for the imagery of Brazilian cinema, strengthening Cinema Novo’s aesthetic ideal.

There lies the restoration crew’s challenge: to bring all of the majesty within the 1964 film into the digital realm, without compromising Glauber’s original intentions and gaze.

Paloma Rocha and Luís Abramo had already worked together with post-production studio Cinecolor, one of the most respected in Latin America, when restoring “Der Leone Have Sept Cabeças” (1971) back in 2011. Ten years later, with “Black God, White Devil”, Cinecolor is a full-fledged partner in the restoration process.

Abramo was responsible for marking and balancing light, based on its original roll. Now he could use digital tools to approximate the 4K scan into that same film. “We tried to create an analogical similarity. We are always pushing only so far as that original reference. And then we can interpret together what the cinematography, and Glauber’s direction were aiming at”, he details.

Renato Merlino, digital restoration coordinator at Cinecolor, was responsible for laying out and establishing what was possible in the process: cleaning (removal of dirt, whites and blacks), analysis and restoration of marks and scratches, depth of field assessment, and, subsequently, execution of a processing tool known as ‘diamond’.

“At Paloma’s request, we didn’t filter the images through any digital ‘camera corrections’. So we don’t interfere with the original shots and framing. If the image was shaky for a given scene, that was a handheld shot, one of Glauber’s decisions. If he shot it by hand, I’m not going to put it on a tripod”, sums up Merlino.

Access to the film’s “first generation”, as he calls the original negative roll, also allowed him to know the level of grain with which the film was photographed. “To give you an idea, current prints that we would see with a film projector, the versions people have seen throughout the years, are ‘fourth generation’ copies”, he explains.

As a result, the new print will be unique. “The digital ‘Black God, White Devil’ that we are going to see has never been seen. People will know how it looked on Glauber’s editing station”, he celebrates.

Rogério Moraes, colorist and restoration technician at Cinecolor, was the person who ensured that the new copy, now digital, preserved the same look seen at the time of release. “We started with an original negative that, technically, was very good. On the technical side, our challenge was to bring forth what was really in the negative during the development process”, he summarizes.

There were many conversations with Walter Lima Jr., who was an actual onset presence, Luís Abramo, and Paloma Rocha. While debating what Glauber had in mind, and Waldemar Lima (the film’s cinematographer) saw, a couple of decisions had to be made, even while preserving the framing and the editing. “We had to think together with Waldemar”, says Moraes, who had been a pupil of the late photographer.

Luís Abramo remembers that “Black God, White Devil” was filmed during mostly cloudy days. Current copies, however, had limited contrast when showing the sky. “We try to keep this historical memory between the negative and our copy. To try and figure out how much color and light balance they wanted when developing their original copies. We need to maintain ethical and technical standards, and try to reflect upon the intentions of their moment, to be faithful to the history of the work itself, in order to make these decisions”, says Abramo.